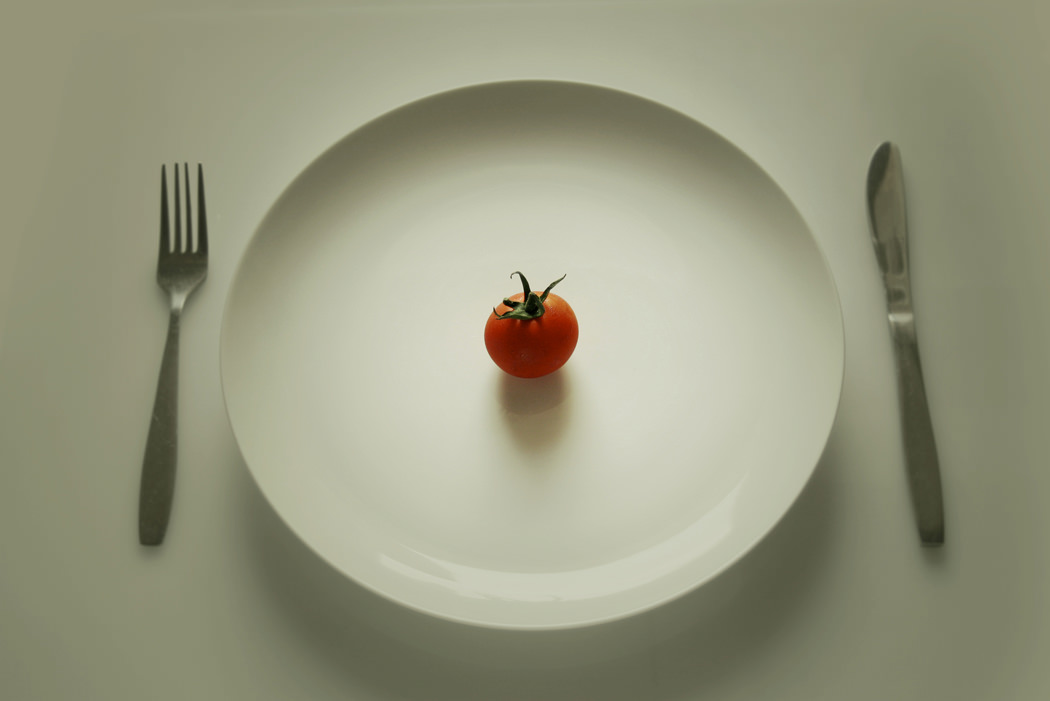

It seems such a simple thing. Here we are in the midst of beautiful, rich farmland, where local farmers are growing delicious vegetables and fruits, raising healthy, tasty livestock and producing cheese, honey and other delicacies. So why don’t we see more of this food on local restaurant tables? The answer is simple … yet surprisingly difficult.

As I’ve learned more about food in Bucks County — and eaten more of it — I’ve become much more sensitive to what appears on my restaurant plate. Last August we were dining locally and steamed asparagus showed up as a side. Asparagus in August? I don’t know where it came from, but I do know it wasn’t nearby. (Asparagus likes spring weather, not the sweltering heat of a Pennsylvania August.) It was also thick with a tough skin. Hardly worth the trip it made from wherever. But even more surprising to me was the chef’s choice — asparagus, in August, when almost every other vegetable was growing within a 10-mile radius.

Connecting restaurants and farmers is harder than it seems. Chefs need quality, consistency and convenience. Bring me good stuff, when I can use it, and to my door. Farmers spend their days, well, farming and don’t have much time or gas money to run around to restaurants making small deliveries.

Despite these obstacles, more chefs are making the effort. In Bucks County, there at least three restaurants – Earl’s Bucks County in Lahaska, and The Down to Earth Café and newly opened Maize Restaurant, both in Perkasie – that are focusing on locally sourced food. On the other side of the river, in Lambertville, Hamilton’s Grill Room and Kindle Café both use local ingredients. I was intrigued. How were they doing it? What I discovered is that we are on the cusp, right here in the Delaware Valley, of a shift in thinking, practice and market demand. It’s been happening in other parts of the country – most notably California – but it’s just gaining momentum in Bucks County.

Despite these obstacles, more chefs are making the effort. In Bucks County, there at least three restaurants – Earl’s Bucks County in Lahaska, and The Down to Earth Café and newly opened Maize Restaurant, both in Perkasie – that are focusing on locally sourced food. On the other side of the river, in Lambertville, Hamilton’s Grill Room and Kindle Café both use local ingredients. I was intrigued. How were they doing it? What I discovered is that we are on the cusp, right here in the Delaware Valley, of a shift in thinking, practice and market demand. It’s been happening in other parts of the country – most notably California – but it’s just gaining momentum in Bucks County.

Ask most chefs why they want locally sourced ingredients and they’ll tell you point-blank it’s about quality and freshness – ultimately translating into better taste. “The food from out-of-state is, on average, coming 1,200 miles,” says Vincent Peterson, the chef and owner of Kindle Café, a vegetarian supper club and caterer in Lambertville. “It’s picked early so it will ripen on the road.” Buying local eliminates the transport time and extra handling. Ingredients are fresher, last longer and taste better. And, many local farmers are growing organic or nearly organic, a selling point with many customers.

Sourcing local also means chefs can be more hands on. “I can talk to the farmers,” says Maize chef Matt McPhelin, who likes to visit area farms to see how they grow, harvest and process the product. “They’ll show me what they have growing nice this season. Then I can plan the menu around that.”

What about the challenges of planning a menu around seasonal availability? Earl’s Bucks County, which recently re-birthed itself with a locally focused menu, plans to change offerings to match the seasons. Maize, open just a short time, has already seen a dozen menu changes, depending on what McPhelin finds on his daily buying trips.

What about the challenges of planning a menu around seasonal availability? Earl’s Bucks County, which recently re-birthed itself with a locally focused menu, plans to change offerings to match the seasons. Maize, open just a short time, has already seen a dozen menu changes, depending on what McPhelin finds on his daily buying trips.

“It demands more creativity from me because I’m working with a limited palette,” Peterson says. “But it also makes my job easier because there are fewer choices.” As a diner, it means you may not find the same items every time you dine at a particular restaurant, but you will know it’s fresh.

Not to be diminished are the benefits that grow from supporting the local economy. “I like knowing that we’re helping local farms and that the money stays local,” says J. Ryman Maxwell, who opened The Down to Earth Café last September. Maxwell uses vegetables and fruit from two nearby farms, Blooming Glen Farm and Penn Vermont. McPhelin gets his meats from Hendricks (Telford), Blooming Glen Pork (Blooming Glen) and Bolton’s (Silverdale).

Maxwell has noticed that even in the short time his café has been open, farmers are coming to him, wanting to sell their goods and asking what products he’d like. Ultimately, this is how it should evolve, he says, with supply shaping itself to demand, and local producers putting themselves on firmer economic footing, knowing what their customers want and will buy. “I’m learning as I go, too,” he says, “I’m learning from the growers and they’re learning from us. The local farmer is realizing, I can branch out. There’s a market for this.”

How does the product get to the restaurant? Ah, therein lies the problem. Most of the chefs go and get it themselves. “It’s nice in theory,” Maxwell says, “but it’s a full-time job to work with all the different growers and farmers.” It takes a lot of coordination and time to meet with people and pick up orders daily or weekly.

Mike Azzara is very familiar with this problem. As manager of the seasonal Lawrenceville (NJ) Farmers Market and as a community outreach worker for the Northeast Organic Farming Association, he knew many farmers and chefs. And both would complain to him. The chefs wanted good-quality, local produce. The farmers wanted to get their goods to the restaurants. So, he decided to take things into his own hands.

Mike Azzara is very familiar with this problem. As manager of the seasonal Lawrenceville (NJ) Farmers Market and as a community outreach worker for the Northeast Organic Farming Association, he knew many farmers and chefs. And both would complain to him. The chefs wanted good-quality, local produce. The farmers wanted to get their goods to the restaurants. So, he decided to take things into his own hands.

In 2008, Azzara began Zone 7, a food distribution company. He picked up goods from 10 farms and delivered it to 15 restaurants, all in Central New Jersey. Last year, the operation grew to include 20 farms in New Jersey and Eastern Pennsylvania and 50 restaurants in Central and Northern New Jersey, putting $200,000 in the hands of local producers and high-quality, fresh goods into the hands of grateful chefs.

Azzara convened a gathering of his farmers and chefs in early February at Nomad Pizza in Hopewell to thank them and share his plans for the coming year. But they did most of the thanking. One after another praised Azzara for his efforts, and for creating Zone 7. As Ted Blew, a family farmer from Pittstown, NJ, put it, “Growing is easy. Putting up a farm stand in front is the next step. But going beyond to restaurants is very hard. It’s expensive. You need a distributor to make it happen. This was the missing link.”

The final “link” is perhaps the most important – the restaurant patron. These chefs and farmers are pioneers, in a way, but ultimately they won’t be successful unless customers buy and enjoy their products, and demand more local goods from the other restaurants and markets. I really should have said something when that asparagus showed up on my plate, but I wimped out. Now, however, I ask more questions, and praise the restaurant when they tell me the food is locally sourced. I guess it’s not enough to simply eat and be merry. If we care about our food, and our local economy, we need to eat and be active.

The final “link” is perhaps the most important – the restaurant patron. These chefs and farmers are pioneers, in a way, but ultimately they won’t be successful unless customers buy and enjoy their products, and demand more local goods from the other restaurants and markets. I really should have said something when that asparagus showed up on my plate, but I wimped out. Now, however, I ask more questions, and praise the restaurant when they tell me the food is locally sourced. I guess it’s not enough to simply eat and be merry. If we care about our food, and our local economy, we need to eat and be active.

Look for Bucks County Taste on Facebook and Twitter!

![What we’re reading [Oct 16 2017]](https://www.buckscountytaste.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/coffee_macbook_reading_pexels-photo-414630-218x150.jpeg)

Great article. It really highlights what most diners don’t realize about what goes into getting good food to their plates. Distribution & Logistics is all about getting a critical mass of stuff moving to make it economical. I’m glad to see that Zone 7 is up and running. It really sounds like a model for other areas with a wealth of good farms and chefs.

Thank you so much for this post. I just visited “Down to Earth Cafe” this morning with my kids. It was awesome and I plan to go back. I live in Perkasie and am also excited to check out Maize.

Good, thoughtful, timely article. Thanks.

[…] Check out Susan S. Yeske’s article in the Bucks County Herald about Perkasie’s newest restaurant, Maize, sourcing from local farms and producers. Learn more about what local restaurants are doing to bring Bucks County produce and food onto their tables in our recent post. […]

Hey Lynne, great article. I submitted it to the news section of care2.com and it made the front page!

http://www.care2.com/news/member/895591921/1408148

Thanks, Brian! I’ve been getting a lot of hits from it. Wondered how it got there. Thanks again.

[…] changes that always accompany development. Read more about this in our post from last February, Getting local food on the local table. "Home is where the hamburger […]

[…] four years ago I wrote an article, Getting local food on the local table, about area chefs who were sourcing locally for their ingredients. I mentioned five restaurants […]